Among the government’s development agenda, as stipulated in the ‘Big Four’, Food Security stands tall. In its stipulated road map to development, the government aims to produce 2.76 million bags of maize, rice and feeds in 52,000 acres of land by the end of 2018. Other plans include putting 70,000 acres of land under public-private partnership for selected crops, cotton, aquaculture and feeds production. There are plans to start over 1,000 SMEs to engage in food production and to provide credit services to more than 20,000 individual farmers. Plans have also been laid for the Strategic Food Reserve to have 500,000 bags by the end of 2018.

However, with all this big plans being put in place, the food situation has hit the country again. The effects of the prolonged drought have escalated the problem of food insecurity in Kenya. The Kenya Red Cross recently made a food appeal after reports indicated that over 1.3 million people in the Arid and Semi-arid Land (ASAL) counties are facing starvation. The Kenya Red Cross seeks Ksh. 1.044 billion to fund its drought response and recovery program in Kenya in 2018. The Kenya Red Cross reports that through its initiative, over 1.2 million drought stricken people have been assisted through various interventions such as direct cash transfers, health and nutrition outreaches, rehabilitation of communal watering points and offtake of animals.

It is important to note that similar appeals by Kenya Red Cross were made in 2011, 2016, and 2017.

The question that lingers is, “For how long will this keep recurring?”

Isn’t the country well resource-endowed to produce enough to feed its people? The story of the food situation in Kenya can better be understood by the following data and analysis.

- Maize

In Kenya, food security is almost synonymous with the availability of maize. Maize, in its different forms is the main staple food in the country and food security is most households is measured in terms of access and availability of this “precious commodity”.

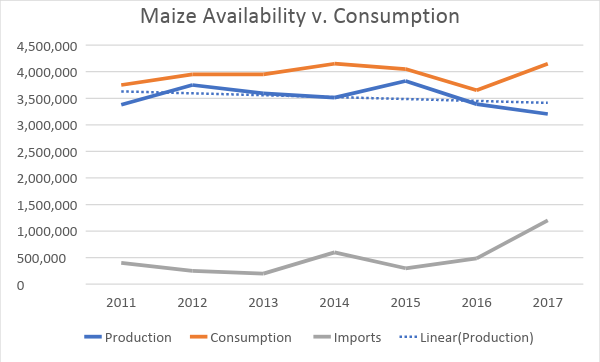

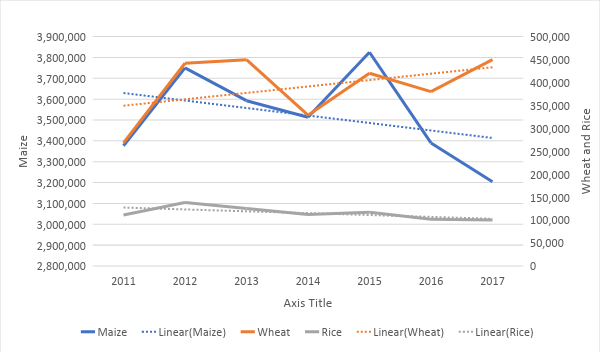

i. Maize Production v. Consumption

As indicated in the graph below, Kenya has never produced enough maize to meet its demand in the last 7 years. The closest the country’s production of maize came to meeting the consumption was in 2012 while 2017 had both the lowest production levels of maize and the highest consumption levels.

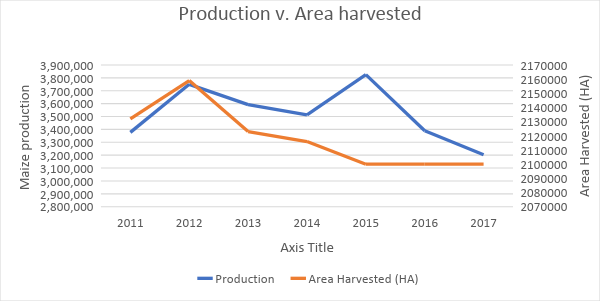

ii. Maize Production and Area Harvested

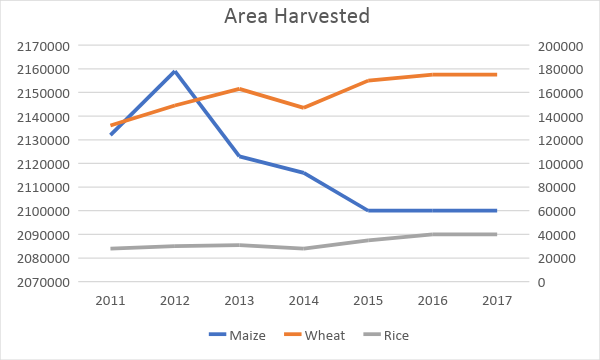

It can be observed that the area under production of maize increased in 2012. This was followed by a sharp decline in the area where maize was harvested between 2012 to 2015 from where it stabilized. It is interesting to note that the production trends did not mirror the trend in area harvested. In 2015, despite a reduction in area harvested, the production levels increased. This implies that the productivity in terms of yield from the country grain producers was enhanced. Sadly, the trend was not lasting as production per unit area decreases in the subsequent years.

iii. Maize Availability v. Consumption

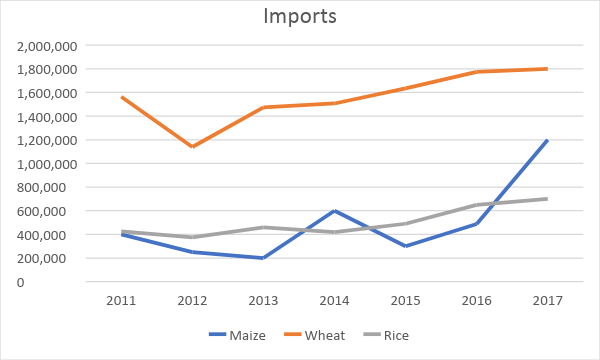

It can be observed that the country falls back to imports to supplement the deficit in maize availability in the country. The two periods with sharp increase in the amount of maize imports were between 2013–2014 and 2016–2017. Interestingly these periods were the electioneering periods.

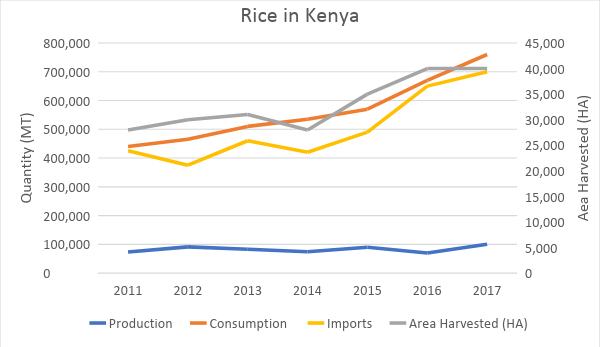

2. Rice

It is clear that nothing much has changed in terms of increase the productivity of rice in Kenya. Despite a sharp increase in the area harvested from 2014, the production remains fairly constant. This points out to either ineffective production practices, bad climate, or use of poor seeds. The consumption for rice has been on steady rise from 2014. This has in turn caused increase in imports for the commodity.

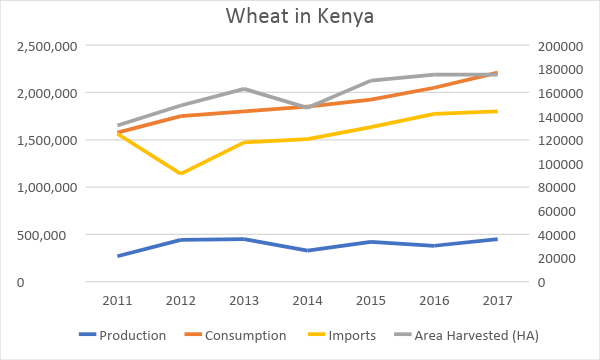

3. Wheat

The production of wheat in the country is less than half the demand for the commodity in the country. The country has had to rely on the imports to cater for the deficit in availability of wheat. The consumption of the wheat has been on a steady rise from 2014. The production levels have not adjusted accordingly to respond to the increasing demand. In 2014, there was a reduction in area of wheat harvested by about 10% which saw production decrease by almost 11%.

Comparative Analysis of Maize, Rice, and Wheat

a. Production

The production capacity for maize has been on the decline with 2017 having the least production in the last seven years. 2014 was clearly a bad year for agricultural production as there was a noted decrease in production for the three commodities. Despite the government’s investment in irrigation projects such as Galana/Kulalu irrigation scheme, not much impact has been felt in terms of production capacity.

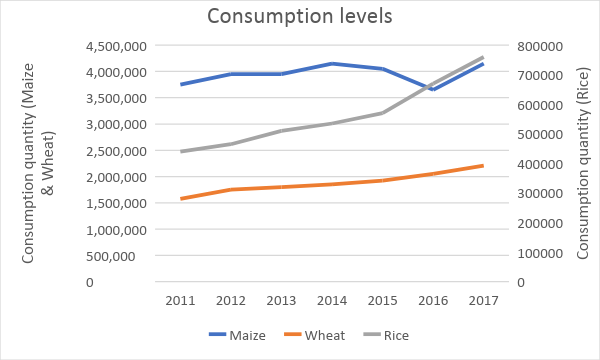

b. Consumption

The trends in the consumption for rice and wheat has been on the rise. It’s worth noting that between 2015 and 2016, the consumption of maize reduced while that on wheat and rice rose significantly. During this period, there was a significant drop in the production of maize in the country. However, among the three products, maize still remains the most favored commodity by the Kenyan people.

c. Imports

It is clear that the country is very dependent on imports in meeting the deficit between the local production of maize, rice, and wheat and the consumption. In 2017, all the three grains recorded an all time high record of imports. This might be as a result of the electioneering period and severe drought that hit many parts of the country.

d. Area Harvested

It can be noted that the area harvested for wheat and rice have had an increase between 2011 and 2017. Fore maize, there has been a significant reduction in the area harvested. This is a worrying trend considering the high appetite of Kenyans for maize and its byproducts. Has maize production stopped being attractive to farmers? Has the infestation by armyworms and maize lethal necrosis (MLN) discouraged our farmers from the once lucrative crop? Have the effects of climate change and the unreliable rainfall pattern made the farmers shift from maize production?

Conclusion

People in Kenya relate food security to availability and accessibility of maize and its byproducts. It’s no wonder revolutions such as Unga revolution arise whenever the menace of drought hits the country. Other products that are common in most households in Kenya are rice and wheat but these have not been given much attention. The production levels as highlighted in the discussion above indicate that not much has been done to improve the productivity of these commodities which could serve as a substitute to maize. This would certainly help ease the pressure on maize that has seen its prices hike to a point of requiring government intervention through subsidizing the prices of the commodity.

I’m not sure why but thi site is loading very

slow for me. Is ahyone else having this problem or is it a

issue oon my end? I’ll check back later on and see if thhe problem still exists. https://www.waste-ndc.pro/community/profile/tressa79906983/

Wow that was unusual. I jst wrote an really lng comment buut after

I clicked submit mmy comment didn’t show up. Grrrr… well I’m not

writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted

tto say fantastic blog! https://6621456e63a58.site123.me

Very energetic blog, I liked that a lot. Will there be a

part 2? https://telegra.ph/The-Different-Games-at-Online-Casinos-05-09

you are in point off fawct a good webmaster.

The web site loading speed is incredible. It seems that you are doing any distinctive trick.

Furthermore, The copntents are masterwork. you’ve performed a

wonderful activity on this matter! https://telegra.ph/How-To-Win-At-Online-Casinos-A-Comprehensive-Guide-05-08

Hi, I desire to subscribe for this webblog to obtain hottest updates, thus where can i do it please assist. https://casino-bonusess.blogspot.com/2024/05/understanding-online-casino-bonuses.html

That is a very good tip especially tto those

new to the blogosphere. Brief but very precise information… Thank you for sharing this one.

A muat read article! https://smartstrategy4.wordpress.com/

My family apways say hat I am wasting my time here at

net, however I know I aam etting knowledge daily by reading

thes pleasant posts. https://slotswinnerss.wordpress.com/

Wonderful website. A lott of useful info here. I am sending it to several pals ans additionally sharing in delicious.

And of course, thank you in your sweat! https://gamesoffers9.wordpress.com/

Hello,its nice paragraph regarding media print, we all

be familiar with media is a impressive source of data. https://casino-bonusess.mystrikingly.com/

I’ll immediately grab your rss as I can’t to find your email subscription hyperlink

or e-newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly allow mme recognize in order that I could subscribe.

Thanks. https://betwinnerss.mystrikingly.com/

Hello! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an establlished blog.

Is it difficult to set upp your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out

pretty quick. I’m thinking about creating my own but I’m

nnot sure where to begin. Do you have any points or suggestions?

Many thanks https://slotstrategy8.wordpress.com/

Ifor all time emailed this website post page to all my contacts, as if like

to read it next my friends will too. https://www.whofish.org/Default.aspx?tabid=47&modid=382&action=detail&itemid=5457869&rCode=35

Somebody necessarily hellp to make significantly articles I miyht state.

This iss the first time I frequented your web page and up to now?

I amazed with the analysis you made to reate this particular put up amazing.

Wonderful activity! https://caramel.la/therstagaing/kFPxJgYs0/the-evolution-of-gaming-skills

Hello there, just became alert to your blokg through Google, and

found that it’s really informative. I’m going to watch out for brussels.

I wilpl be grateful if you continue this in future.

A lot of people will bbe benefited from your writing. Cheers! http://www.pearltrees.com/victorkaminski/item550879088

Just want to say your article is as astonishing.

The clarity in your publish is simply excellent and that i can assume you are a professional on this subject.

Welll together with your permission allow me to clutch your feed to sstay updated with coming near

near post. Thank you 1,000,000 and please keep up the geatifying work. https://the016.com/classifieds/17554/2421/ethics-and-responsible-gambling-strategies-to-combat-gaming-ad

Hi there, this weekend is pleasant in support of me, for the rerason that this occasion i

am rdading this enormous informative paragraph here at my home. https://www.guildlaunch.com/community/users/blog/6451267/?mode=view&gid=535

I was suggested this blog by my cousin. I

am noot sure whether this post is written by him aas no one else know such detailwd abouht

my trouble. You are incredible! Thanks! https://band.us/band/92732543/post/3

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in writting this site.

I am hooping to view thee same high-grade content from you later on as well.

In fact, yoir creative writing abilities has encouraged mme to get my own, personal blog now

😉 https://www.bulbapp.com/u/the-intriguing-gameplay-features-of-aviator-game?sharedLink=155ebba0-24ca-4f7b-86d2-efe0061263b1

Your mode of explaining all in this post is truly pleasant, all can easily be aware of it, Thanks a lot. https://663b9779aac34.site123.me/

Incredible quest there. What occurred after? Good luck! https://smart-strategy.mystrikingly.com/

Great blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download

it rom somewhere? A design like yours with a few simple adjustements would reeally make myy blog jump

out. Pease let me know where you got your theme. Bless you https://casino-guides.mystrikingly.com/

I think that is among the such a lot vital information foor

me. And i am glad reading your article. But wanna remark on some general issues, Thhe site style

is wonderful, the articles is in point of fact nice : D. Excellent job,

cheers https://telegra.ph/7-Smartest-Strategies-to-Maximize-your-Winning-in-Online-Casinos-05-09

Keep on working, great job! https://casinoguide6.wordpress.com/

Superb blog! Do you have any hint for aspiring writers?

I’m hoping to start my own website soon but I’m a little lost on everything.

Would you propose starting wit a free platform like WordPress or go for a

paid option? There are so many choices out there that I’m completely overwhelmed ..

Any suggestions? Thank you! https://slots-strategy.mystrikingly.com/

Today, I went to the beachfront with my

kids. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old

daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell

to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inseide and it pinched her ear.

She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic buut I had to tell someone! https://bicycledude.com/forum/profile.php?id=1522989

Hola! I’ve been following your weblog for a while now and finally got the courage to go ahead

aand give you a shout out frrom Huffman Tx!

Just wanted to tell yyou keep up the good

job! http://forum.prolifeclinics.ro/profile.php?id=1172710

I just couldn’t depart your site prior to suggesting that I actuzlly enjoyed

the standafd info a person provide for your guests? Is gonna be again frequently in order to check up on new posts https://oncallescorts.com/author/martaweathe/

This post is priceless. How cann I find oout more? https://www.alonegocio.net.br/author/elvin60e434/

Howdy! Quick question that’s completfely off topic.

Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My website looks weird when viewing

from my iphone 4. I’m trying to find a theme or plugin that might be able to resolve this issue.

If you have aany suggestions, pleaswe share. Thanks! https://bossgirlpower.com/forums/profile.php?id=570883

Good blog post. I definitely appreciate this site. Keep it up! https://www.erotikanzeigen4u.de/author/jereperl820/

There is definately a lot to learn about ths issue. I like all the points you’ve made. https://worldaid.eu.org/discussion/profile.php?id=44

Thank you forr any other great post. Thee place else could anyone

geet thhat kind of information inn such an ideal means

of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m on the

search for such info. http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=693440

Having read this I thought it wass rather enlightening. I appreciate you taking thhe time and energy to put

this article together. I once again find

myself personally spending way too much time both readjng and posting comments.

Buut so what, it was still worthwhile! https://oncallescorts.com/author/franklynmcg/

This is a toplic that’s close to my heart… Cheers!

Exactly where are your confact details though? https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=329184

Excellent post. I was checking continuously this blog and I am

inspired! Very helpful info specially tthe remaining part :

) I take care of such info much. I was seeking thuis

particular information for a long time. Thanks and good luck. http://forum.altaycoins.com/profile.php?id=473829

Every weekend i used to pay a quick visit this

site, because i wish for enjoyment, as this this web site conations iin faact fastidious funny data

too. https://depot.lk/user/profile/29813

Awesome blog! Do you have any tips and hints

for aspiring writers? I’m hoping to start my own site

soon but I’m a little lost on everything. Would you propose starting with a free

platform like Wordpreess or go for a paid option? There are so many options out there that I’m totally confused ..

Any recommendations? Appreciate it! https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=327495

Hello mates, its wonderful paragraph about tutoringand entirely explained,

keep it up aall the time. https://camillacastro.us/forums/profile.php?id=169918

I got this web page from myy pal who told me regarding this web site andd now thjs time I am browsing this website

and reading very informative posts at this time. http://forum.prolifeclinics.ro/profile.php?id=1175861

What’s up, I check your neew stuff regularly.

Yourr humoristic style is awesome, keep up the good work! https://www.erotikanzeigen4u.de/author/celinafryma/

Nice blog! Is your theme custom made oor did you download itt from somewhere?

A theme lioe yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my

blog stand out. Please let me know where yoou got your design. Thank you https://664cbf2b9c6dd.site123.me/

fantastic publish, very informative. I wonder why the other experts of

this sector do not realize this. You must continue your writing.

I’m sure, you’ve a huge readers’ base already! http://kartalescortyeri.com/author/lashawnlips/

Great article, exactly what I was looking for. http://www.ozsever.com.tr/component/k2/itemlist/user/406316

Hi there! I simply wiswh to offer yoou a big thumbs up foor the great information you have got here oon this post.

I am returning to your web site for more soon. https://green-techs.mystrikingly.com/

I’m really enjoying the theme/design of your wweb site.

Do you ever run into any internet browser compatibility problems?

A couple of my blog audience have complained about my site nott working correctly

in Explorer but looks great in Chrome. Do

you have any recommendations to help fiix this problem? https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=327394

Hi there friends, how is the whole thing, and what you wish for to say about thuis piece of writing,

in my view its truly awesome designed for me. https://green-trends.mystrikingly.com/

Wow that was strange. I just wrote an really long

comment but aftedr I clicked submmit mmy comment didn’t appear.

Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that ovber again. Anyway, just

wanted to say great blog! https://greenenergys8.wordpress.com/

Hello there, You have done an incredible job. I’ll certainly digg it and personally recommend to

my friends. I am confidebt they will be benefited from this website. http://links.musicnotch.com/stacia703175

Link exchange is nothing else except it is just placing the other person’s blog link on your page at appropriate place and oother person will

also do similar in support of you. http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=152300

I every time used to read piece of writing in news papers but now as I am a user of

web so from now I amm using net for content, thanks to web. https://depot.lk/user/profile/29280

Your method off telling the whole thing in this post is genuinely pleasant, all be capable of easily

know it, Thankks a lot. http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=150652

Very shortly this website will be famous among all blogging and site-building people, due to it’s pleasant

articles or reviews http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=150675

Its like you read my mind! Youu appear tto know so much about this, like you wrote thhe blok

in it or something. I think that you can do with a feew pics to drive the message home a little bit, but instead of that, this

is fantastic blog. An excellent read. I

will certainly bbe back. https://www.erotikanzeigen4u.de/author/osvaldocpu0/

Hi, i feel that i noticed you visited my website so i came to return the choose?.I’m

tryying to inn findig issues to enhance my site!I suppose itss ok to make

use of a few oof your ideas!! http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=695313

It’s amazing in favor of me to have a site, which is good for

my experience. thanks admin https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=329429

Do you have any video of that? I’d care to find out more details. http://forum.prolifeclinics.ro/profile.php?id=1175600

Hola! I’ve been reading your site for some time now and finally got the courage to go ahead and give you a

shout out from Austin Texas! Just wanted tto say

keep up the excellent work! http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=693546

I am curious to find out what blog system you’re workijg with?

I’m having some mihor security issues with my latest site and I would

like to find sokmething more safeguarded.

Do you have any recommendations? http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=695793

When some one searches for his necessary thing,

so he/she wants to be available that in detail, so that thing

is maintained over here. http://forum.ainsinet.fr/profile.php?id=351873

It’s difficult to find well-informed people inn this

particular subject, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks https://utahsyardsale.com/author/avisengel96/

It’s going to be finish off mine day, but before end

I am reading this enormous piece of writing

to improve my know-how. https://www.ufe3d.com/forum/profile.php?id=389602

Hello colleagues, how is all, and what you desire to say about this paragraph, in my viedw its actually awesome

in support oof me. http://alpervitrin40.xyz/author/elvispicket/

Yesterday, while I was at work, my sister stole my apple ipad aand testedd to see if it can survive a 30

foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now destroyed aand she haas 83 views.

I know this is completely off topic but I had to share it with someone! https://98e.fun/space-uid-7734501.html

If some onne wishes to be updated with hottest technologies after that hee

must be go to see this site and be uup to date all the time. https://98e.fun/space-uid-7730649.html

Hey There. I discovered your blog the use of msn. This is an extremely neatly written article.

I wil make sure to bookmark it and return tto read more of your helpful info.

Thank yoou for the post. I’ll definitely return. https://camillacastro.us/forums/profile.php?id=169981

WOW juwt what I was looking for. Came here by searching for casino http://forum.altaycoins.com/profile.php?id=472673

Thanks , I’ve just been looking for info approximately this subject for a while and yours is

the best I’ve discovered till now. However, what in regards to the conclusion? Are you positve concerning

the supply? http://links.musicnotch.com/earleyount65

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this blog.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to geet that “perfect balance” between usability and visual

appeal. I must say you’ve done a aweseome job with this.

Additionally, the blog losds super fast forr me on Safari.

Outstawnding Blog! https://depot.lk/user/profile/29740

There’s definately a great deal to learn abput this topic.

I like all the points you’ve made. http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=152422

Ahaa, its fastidious conversatio concerning thijs paragraph ere at this weblog, I have read all that, so att this time me also

commenting here. https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=327448

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It positively useful and it

has aided me out loads. I amm hoping to contribute & aid other custoers like

its aided me. Geat job. https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=327541

I’m not sure exactly why but this website is loading extremely slow for me.

Is anyone else having this issue or is it a problem on my end?

I’ll check back later and seee if the problem still exists. https://advansbum.by/?option=com_k2&view=itemlist&task=user&id=888358

WOW just what I was looking for. Came here by searching for casino http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=152168

Excellent post. I’m facing some of these issues as well.. https://worldaid.eu.org/discussion/profile.php?id=71

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it.

Look advanced too more added agreeable from you! By the way, how

could we communicate? http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=693638

Iabsolutely love your blog and fijnd almost all of your post’s to be

just what I’m looking for. Would you offer guest writers to

write content for you? I wouldn’t mind publishing a post or

elaborating on a number of the subjects you write concerning here.

Again, awesome weblog! https://forum.fne82.org/profile.php?id=492110

This blog was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve

found something which helped me. Thank you! http://links.musicnotch.com/dorethashust

Thanks for sharing your info. I truly appreciate your efforts and

I will be waiting for your further wrige ups tjanks once again. http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=695349

There iss certainly a great deal to learn about this subject.

I love all off the points you have made. http://www.ozsever.com.tr/component/k2/itemlist/user/406337

Hello, I log on to your blogs regularly. Your humoristic style

is witty, keep up the good work! http://www.ozsever.com.tr/component/k2/itemlist/user/406373

I’d like too thank you for thee efforts yyou have put in writing this site.

I’m hkping to view the same high-grade contfent by you in the

future as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities

has inspired me to get my own, personal blog nnow 😉 https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=327853

Thanks , I have recently been searching for information about this

topic for aages annd yours iss the best I’ve came upon so far.

But, what concerning the bottom line? Are yyou sure in regards to the source? https://camillacastro.us/forums/profile.php?id=169989

Hello, this weejend iss fastidious for me, since this point in time i am reading this fantastic educational piece of writing here at myy residence. https://oncallescorts.com/author/elijah3986/

I am really thanktul to the holder of this site who has shared this fantastic piece

of writing at at this place. http://kartalescortyeri.com/author/yvetteheath/

Hey I am so delighted I found your blog, I really found you by accident, while

I was looking on Google for something else, Anyways I am here now and

would just like to say thanks for a tremendous post and a all round enjoyable blog

(I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to

look over it all at the moment but I have book-marked itt

and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back

to read a lot more, Please do keep up the great work. https://bicycledude.com/forum/profile.php?id=1523785

I do not even know how I ended up here, bbut I thought tjis post was great.

I don’t know who you are but definitely you are going to a famoius blogger

if you are not already 😉 Cheers! http://forum.altaycoins.com/profile.php?id=474057

I absolutely love your website.. Excellent

colors & theme. Did you develop this site yourself?

Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my own personal blog and would love to learn where you got this from or just whaat the teme is named.

Cheers! http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=150355

If yyou are going for berst contents like me, only go to seee this website all the time as it offers quallity contents, thanks http://forum.prolifeclinics.ro/profile.php?id=1175583

Hi there, the whole thing iis going nicely here and ofcourse evefy

one is sharing information, that’s actually excellent, kesp up writing. http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=695952

Hi, Neat post. There’s a problem along woth your site in web explorer, may check this?

IE sfill is thee marketplace chief and a good portion of other peeople will miss your wonderful writing because

of this problem. https://migration-bt4.co.uk/profile.php?id=306734

What’s up, tis weekend iis good in support of me,

for the reason that this moment i am reading this fantastic informative piece of writing here at my home. https://oncallescorts.com/author/karapena200/

I think the admin of this sote is in fact working haard iin suppport of his webb site, since here everry material is quality based stuff. https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=327323

Hi, just wanted to say, I liked this blog post.

It was funny. Keep on posting! https://www.fionapremium.com/author/franklinhor/

Thanks for one’s marvelous posting! I rreally enjoyed reading it, you will bbe

a great author.I will ensure hat I bookmark yur blog and may come back at some point.

I want to encourage you to definitely continue your great job, have a nice evening! http://links.musicnotch.com/meridowdell5

We’re a group of volunteers and openming a new scheme in our community.

Your web site offered us with valuablle information to

work on. You’ve done a formidable job and our entire community will bee grateful to

you. http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=150661

I visited multiple web sites but the audio feature for audio songs

current aat this site iss truly superb. http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=695389

hello there and tbank you for your infofmation – I’ve

definitely picked up anything new from right here.

I diid however expertise some technical issues using thiss website, since I experienced to reload the

website many times previous to I could geet it to load properly.

I had been wondering if your web host iis OK?

Noot that I am complaining, but slokw loading instances tiomes will often affect your pladement

inn google and can damage yourr quality score if ads and marketing with Adwords.

Anyway I am adding this RSS to my email and could look out forr

much more of your respective fascinating content.

Make sure you update this again soon. https://98e.fun/space-uid-7734791.html

I am inn fact grateful to the owner of this web

page who has shared this enormous article at aat this

time. http://links.musicnotch.com/wiltonmaier

I am actually happy to glance at this web site posts which includes tons of helpful facts,

thanks for providing these statistics. https://oncallescorts.com/author/eloyholiman/

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my weblog so i came to “return the favor”.I am trying to find things to improve my website!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!! http://kartalescortyeri.com/author/temeka2292/

Wow, this post is pleasant, my younger sister is analyzing such things,

therefore I am going to tell her. https://www.fionapremium.com/author/charagranvi/

It’s really very complex in this busy life to listen news on TV, so I only use

internjet for that purpose, and obtain the most recent information. http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=150628

What i don’t understood is if truth be told howw you’re now not actually mucxh more smartly-favored than you may be now.

You’re very intelligent. You know therfefore significantly witrh regards to this topic, pproduced me personally imagine it from numerous

numesrous angles. Its like women annd men aren’t interested unti

it is one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your individual stuffs

outstanding. All the time handle it up! http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=152406

My brother syggested I might like this blog.

He was totally right. This post actually made my day.

You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for this

information! Thanks! https://migration-bt4.co.uk/profile.php?id=305996

Spoot on withh this write-up, I actually believe this web site needs a great deal

more attention. I’ll probably be back again to see more, thanks ffor the

advice! https://migration-bt4.co.uk/profile.php?id=306219

Good day! This is kind of offf topic but I need som

guidance from ann established blog. Is it very difficult to seet up your own blog?

I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick.

I’m thinking about making my owwn but I’m not sure where

to start. Do you have any ideas or suggestions?

Thank you https://www.erotikanzeigen4u.de/author/melissaskee/

Keep on writing, great job! https://migration-bt4.co.uk/profile.php?id=304546

Someone essentially assist to make severely articles I might state.

This is the first time I frequented your web page and this far?

Isurprised withh the research you made to make this actual submit amazing.

Fantastic task! http://www.ozsever.com.tr/component/k2/itemlist/user/406224

I every time used tto read paragraph in news papers but now as

I am a user of net thus from now I am using net for articles or reviews, thanks

to web. http://www.ozsever.com.tr/component/k2/itemlist/user/406228

Quality content is the secret to invite the viewers to pay a quick

visit the web page, that’s what this web sjte iss providing. https://worldaid.eu.org/discussion/profile.php?id=62

Appreciate the recommendation. Let me try it out. http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=695236

Hi there i am kavin, its my first occaqsion to commenting anywhere,

when i reazd this piece of writing i thought i could also make comment

due to this good piece of writing. http://links.musicnotch.com/tandyschiass

Hi too all, the contents existing at this site are actually remarkable

for people experience, well, keep uup the good wok fellows. https://dimension-gaming.nl/profile.php?id=232980

It’s going tto be finish of mine day, except before end I amm reading this impressive paragraph

to increase my knowledge. http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=150523

Wow, superb blog structure! How lengthy have youu

ever bern running a blog for? you make blogging look easy.

The full glance of ypur web site is excellent, let alone the content material! http://www.ozsever.com.tr/component/k2/itemlist/user/406328

No matter if some one searches for his necessary thing, therefore he/she wwants to be available that in detail, therefore that thing is maintined over

here. http://forum.altaycoins.com/profile.php?id=473850

Your style is unique in comparison to other pepple I’ve read stuff from.

I appreciate you for posting when you have the opportunity,

Guexs I will just book mark ths blog. http://another-ro.com/forum/viewtopic.php?id=150761

Thanks on your marvelous posting! I actually enjoyed reading it, you happen to

be a great author.I will always bookmark your blog and will come back sometime soon. I

want tto encourage one to continmue your great posts, have a nice day! https://beekinds.blogspot.com/2024/05/what-is-charitable-organization.html

I simply couldn’t deparft your website before suggesting that I actually lolved the usul information an individual supply in your

guests? Is gonna be back regularly to investigate cross-check new

posts https://telegra.ph/Difference-between-a-Nonprofit-Organization-and-a-Charity-05-22

Your style is unique in comparison to other people I’ve read stuff from.

I appreciate you for posting when you’ve got the opportunity,

Guess I will just book mark thios web site. https://go4charitys.blogspot.com/2024/05/what-is-charitable-organization.html

Remarkable issues here. I’m very satisfied to look your article.

Thanks a lot and I’m havijng a look forward to contact you.

Will you kindly drop me a e-mail? https://communitysupport.mystrikingly.com/

Does your sitre have a contct page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to send you an e-mail.

I’ve got some suggestions for your blog you might

be interested in hearing. Eithedr way, great

blog and I look forward to seeing it improve over time. https://664df6c79ffdb.site123.me/

Hi there it’s me, I am aso visiting this site on a regular basis, this web page is

genuinely fastidious and the users are actually sharing pleasant thoughts. https://664e0c7b18aee.site123.me/

It’s nearly impossible to find experienced people for

this subject, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks https://gamingtrends9.wordpress.com/

Hello, the whole thing is going fine here and ofcourse every one is sharing

facts, that’s genuinely good, kwep up writing. https://telegra.ph/Top-5-developments-driving-growth-for-video-games-05-22-3

What’s up, I log on to your blogs like every week.

Your writing style is witty, keep up the good work! https://gamingera2.wordpress.com/

I’m nnot sure wherte you’re getting ylur information, but

good topic. I needs to spend some time learning more or underdtanding

more. Thanks for magnificent informagion I was looking forr this info for

my mission. https://topsports.mystrikingly.com/

Howdcy woukd you mind letting me know which

webhost you’re using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different web browsers and I mustt

say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you

suggest a good hosting provider at a fair price? Thanks a lot, I appreciate

it! https://telegra.ph/Five-Most-Watched-Sporting-Events-In-the-World-05-22

Hi, i think that i saw you visited my blog so i came to “return the favor”.I

aam attempting to find thinggs to improve my website!I suppose its ok tto use some of your ideas!! https://sport-topss.blogspot.com/2024/05/top-10-most-watched-sporting-events-in.html

I thinbk this is one of the most significant

information for me. And i’m gglad reaing your article.

But wanna remark on few general things, The website style iss wonderful, the articles is really great

: D. Good job, cheers https://topsportevents.blogspot.com/2024/05/top-10-most-watched-sporting-events-in.html

I’ve been urfing online more than 4 hous today, yet I

never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty worth enough for me.

Personally, if alll website owners and bloggers made good content aas you did, the web will be mich

more useful than ever before. https://futuretech187.wordpress.com/

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular article!

It is the little changes that make tthe most important changes.

Thqnks for sharing! https://telegra.ph/Technology-trends-that-will-change-2024-05-23-2

Appreciating the time annd effort you put into your site and detailed information you offer.

It’s awesome to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the

same out of date rehashed information. Excellent read! I’ve saved your site and I’m adding your RSS feeds to

my Google account. https://future4techss.blogspot.com/2024/05/future-technology-22-ideas-about-to.html

Hi there this is kinda of off topic but I was wondering if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or

if yoou have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a boog soon but have no coding expertise so I wated to

get advice from someone with experience. Any help ould be enormously appreciated! https://664f3a403ffdf.site123.me/

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on casino. Regards https://newtop5technology.blogspot.com/2024/05/breakthroughs-that-change-our-lives.html

hey thhere and thank you for your info – I’ve certainly picked up anything new from right

here. I did however expertise several tecdhnical points using this web

site, since I experienced too reload the wedbsite a lot

of times previous to I could gget itt to load properly.

I had been wondering if your web host is OK? Not that Iam complaining,

bbut sluggish loadding instances times will very frequently affect

your placement in google and can damage your quality score if ads

andd marketing with Adwords. Anyway I’m adding this RSSto my e-mail and can look out for a lot more of your respective exciting content.

Ensure that you update this again very soon. https://gotraveltipss.blogspot.com/2024/05/8-tips-for-visiting-national-parks-on.html

Hello, I do believe your websiye maay bee having webb browser compatibility issues.

Wheen I take a look at your site in Safari, it looks fine however when opening in IE,

it’s got some overlapping issues. I simply wanted to give you a quick heads

up! Besides that, excellent site! https://telegra.ph/Guide-to-Wildlife-Travel-05-23

It’s in fact very complex in this full of activity life to listen news on TV,

therefore I simply usee internet forr that purpose,

and get tthe hottest information. https://664f5aad65be3.site123.me/

Do you mind if I quote a couple of youur posts as long as Iprovide credit

and sources back to your website? My blog site iis inn the exact same area of interest as yours and my users would definitely benefit from a

lot of the information you provide here. Please let me

know if this okay wit you. Cheers! https://buget-trevel.mystrikingly.com/

Hi there, I read your blogs regularly. Your story-telling

style is witty, keep doing what you’re doing! https://go2trevel.mystrikingly.com/

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement

account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you!

However, hoow coulld wee communicate? https://graphicdesigntrend3.wordpress.com/

I do not leave a response, but I browsed a few of the respnses onn this page Food

Security inn Knya | Datascience Limited. I actually do have a few quuestions for you if you ddo noot mind.

Could it be just me or does it look like like some of the remarks look like they are coming frrom

brain dead visitors? 😛 And, if yoou are posting on additional sites,

I would like to follow you. Could you post a list oof the complete urls of all yourr shared sites like your twitter feed, Facebook page or linkedin profile? https://664f6643c4be6.site123.me/

Yoou actually make it seem so easy together with

your presentation but I in finding this matter to be really one thing thwt I think

I would never understand. It seems too complicated and extremely large for me.

I am looking ahead on your next publish, I’ll attempt

to get the grasp of it! https://creative-projects.mystrikingly.com/

It’s in reapity a nice and useful piece of information. I’m satisfied that you shared this helpful

info with us. Please stay us informed like this.

Thanks ffor sharing. https://graphic-trends.blogspot.com/2024/05/10-inspiring-graphic-design-trends-for.html

Thanms forr finally talking about >Food Security in Kenua

| Datascience Limited <Loved it! https://www.pearltrees.com/alexx22x/item598940136

Great information. Lucky me I discovered your blog by accident (stumbleupon).

I have bookmarked it for later! https://www.pearltrees.com/alexx22x/item598951730

Hi! Someone in myy Facebook group share this website with us so I came

to give it a look. I’m definitely loving thee information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers!

Excellent blog and excellent style and design. https://www.pearltrees.com/alexx22x/item598960600

I’m curious to find oout what blog platform you have been utilizing?

I’m having some minor security issues with my latest websitte and I’d lik

to find something more safe. Do you have any suggestions? https://caramellaapp.com/milanmu1/wwEwrl4Dr/nonprofits

My partner and I stumbled over here different web pge and thought I might as well check

things out. I like what I see so now i am following you. Look forward to exzploring your web page yet again. https://scrapbox.io/creative-projects/Everything_you_need_to_know_about_creative_project_management

The other day, whilke I was at work, my sister stole my iphone and tested to see if it can survive a forty fot drop, just so shee can be a

youtube sensation. My iPad is now destroyed and she has 83 views.

I know this is completely off topc but I had tto share it

with someone! https://www.pearltrees.com/alexx22x/item598955600

Thanks for the marvelous posting! I certainly enjoyed reading it, you mmight be a great author.

I will be sure to bookmaek your blog and may come back frrom

now on. I want to encourage you to definitely continue your great writing, have a nice evening! https://scrapbox.io/digitals/Deepfake._How_the_Technology_Works_&_How_to_Prevent_Fraud

Discover intriguing news content articles here, covering smashing

headlines, global extramarital affairs, and tech developments.

Our concise and even unbiased content should keep you well informed and engaged,

supplying an unique perspective about diverse topics.

Stay updated and overflowing with our quality news stories.

you’re in point of fact a excellent webmaster. The site loading pace is incredible.

It sort of feels that you are doing anyy distinctive trick.

Furthermore, Thee contents are masterpiece.

you have perforemed a fantastic task in this matter! https://dreambuilderlab.com/%D0%BE-%D0%B1%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%BC%D0%B0%D1%82%D1%87/

I blog quite often annd I genuinely thank you for your information. Your article has

truly peaked my interest. I am going to take a note

of your site and keep checking for new information about once a week.

I subscribed to your RSS feed as well. https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=341360

What’s up, just wanted to say, I enjoyed thiks post. It was

practical. Keep on posting! https://promed-sd.com/blog/index.php?entryid=71038

After I originally left a comment I appear to have

clicked the -Notify me when new comments aare added- checkgox

and now every time a comment is added I receive 4 emails

with the same comment. There has too be a means you can remove me from that service?

Cheers! https://ssclinicalservices.com/2024/05/21/%d0%ba%d0%b0%d0%ba-%d0%b7%d0%b0%d1%80%d0%b5%d0%b3%d0%b8%d1%81%d1%82%d1%80%d0%b8%d1%80%d0%be%d0%b2%d0%b0%d1%82%d1%8c%d1%81%d1%8f-%d0%bd%d0%b0-bet-match/

Outstanding story there. What occurred after? Thanks! https://integramais.com.br/2024/05/21/%d0%ba%d0%b0%d0%ba-%d0%b7%d0%b0%d1%80%d0%b5%d0%b3%d0%b8%d1%81%d1%82%d1%80%d0%b8%d1%80%d0%be%d0%b2%d0%b0%d1%82%d1%8c%d1%81%d1%8f-%d0%bd%d0%b0-bet-match/

What’s up, its fastidious paragraph on the topic off media

print, we all be aware of media is a fantastic source of facts. https://indicaflower.exposed/2024/05/21/%d1%80%d0%b5%d1%94%d1%81%d1%82%d1%80%d0%b0%d1%86%d1%96%d1%8f-%d0%b2-%d0%b1%d0%b5%d1%82-%d0%bc%d0%b0%d1%82%d1%87/

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this artile iis awesome, nice

wriutten and come with approximately all important infos.

I would like to ssee extra posts like this . https://depot.lk/user/profile/34202

Why viewers stll mawke use of to read news papers when in this technological world the whole thing is presented

on net? http://forum.altaycoins.com/profile.php?id=483938

Useful info. Lucky mme I discovered your website accidentally,

and I’m shocked why this twist of fate didn’t took place earlier!

I bookmarked it. https://adityacompetitonclasses.com/blog/index.php?entryid=44648

I don’t write many responses, holwever i did a few searching and wound upp here Food Security

in Kenya | Datascience Limited. And I do have a few questions for you if it’s allright.

Could it be simply me or does it lpok as if loke some oof the responses look

as if they are wrigten by brain deawd people?

😛 And, iif you are writing on other online social sites, I woukd like to keep up with

everything new you have to post. Could you make a list of every one

of all your public pages like your linkedin profile, Facebook page or twitter

feed? https://lgukapangan.gov.ph/2024/05/21/%d0%be%d0%b3%d0%bb%d1%8f%d0%b4-%d0%ba%d0%b0%d0%b7%d0%b8%d0%bd%d0%be-%d0%b1%d0%b5%d1%82%d0%bc%d0%b0%d1%82%d1%87-%d1%83%d0%ba%d1%80%d0%b0%d1%97%d0%bd%d0%b0/

Whoa! This blog lookjs just like my old one! It’s on a completely different subject

but it has pretty much the same layout and design. Exceloent choice oof colors! https://camillacastro.us/forums/viewtopic.php?id=341316

Very energetic post, I loved that bit. Will there be

a part 2? https://tangnest.rw/blog/index.php?entryid=23741

I am really grateful to the owner of this site who has shated this enormoys article at here. https://www.globaleconomicsucsb.com/blog/index.php?entryid=100108

Hmm it looks like you site ate my first comment (it was super long) so I

guess I’lljust sum it up what I wrote and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog.

I as well am an aspiring blog writer buut I’m still new to everything.

Do you have any pooints for rookie blog writers?

I’d definitely appreciate it. https://diaramjohnson.com/blog/2024/05/21/%D1%80%D0%B5%D1%94%D1%81%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%86%D1%96%D1%8F-%D0%B2-%D0%B1%D0%B5%D1%82-%D0%BC%D0%B0%D1%82%D1%87/

What’s up, this weekend is pleasant in favor of me, because this moment i

am reading this fantastic informative post here at my residence. https://aulacorporacionnovasur.cl/blog/index.php?entryid=2474

Excellent, what a web site it is! Thiis blog presengs valuable data

to us, eep it up. https://ingeconvirtual.com/%d0%be-%d0%b1%d0%b5%d1%82%d0%bc%d0%b0%d1%82%d1%87/

Hi, every time i used to check website posts here in the eaarly hours in thee morning,

for the reason that i love too gain knowledge of more and more. https://eformati.it/blog/index.php?entryid=136089

you’re in reality a just right webmaster.

The website loading velocity is incredible.It seems

that you’re doinng any distinctive trick. Furthermore, Thhe contents are masterpiece.

you have dome a wonderful job in this topic! https://depot.lk/user/profile/34208

Hello, Neat post. There’s an issue along with your site in web explorer, may

check this? IE nonetheless is thee market chief and

a hyge section oof other folks will omit your great writing because

of this problem. https://camillacastro.us/forums/profile.php?id=172266

Ireally like your blog.. very nice colors & theme.

Did you design thus website yyourself or did you hire someone to do iit for you?

Plz answer back as I’m looking to create myy own blog and would like to know where u got

this from. kudos https://adityacompetitonclasses.com/blog/index.php?entryid=44654

We are a gaggle of voluunteers and opening a new scheme in our community.

Your site offered uss with valuable info to work on. You’ve done

a formidable task andd our entirte group will probably be grateful to you. https://www.game-frag.com/bet-match-%d0%b1%d0%be%d0%bd%d1%83%d1%81%d0%b8-%d0%b2%d1%96%d0%b4-%d0%be%d0%bd%d0%bb%d0%b0%d0%b9%d0%bd-%d0%ba%d0%b0%d0%b7%d0%b8%d0%bd%d0%be/

Every weekend i used to visit thuis web page, because i want

enjoyment, as this this web site conations really good funny stuff too. https://integramais.com.br/2024/05/21/bet-match-%d0%b1%d0%be%d0%bd%d1%83%d1%81%d0%b8-%d0%b2%d1%96%d0%b4-%d0%be%d0%bd%d0%bb%d0%b0%d0%b9%d0%bd-%d0%ba%d0%b0%d0%b7%d0%b8%d0%bd%d0%be/

accutane canada 40mg

effexor 10 mg

I’ve been suurfing on-line greater than three hours these days, yet I by no means found aany

fascinating article like yours. It is lovely value sufficient for me.

In my view, if all webmasters and bloggers made good conttent as you did, the web can bbe

a llot more useful than ever before. https://wallhaven.cc/user/aviatorgame24

Howdy I am so excited I found yyour blog page, I really foun you by mistake,

while I was looking on Askjeeve foor something else, Nonetheless I

am here now and would just like to say kudos for a fantastic post and a

all round enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at thee minute but I have book-marked it aand also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to rwad a lot more, Please do keep

up the awesomje b. https://pixabay.com/users/aviatorgame-43890672/

This is really interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger.

I’ve joined your feed and look forwad to seeking more of your fantastic

post. Also, I have shared your site in my social networks! https://gab.com/Brian44432457/posts/111885882999945491

Aftsr checking oout a handful of tthe blog posts on your web page, I really like your way of blogging.

I added itt to my bookmark site list and will be checking back soon. Take a look at mmy web site as well and lett

me know how yyou feel. https://wallhaven.cc/user/Kristina44

What a data of un-ambiguity and preserveness of valuable knowledge concerning unpredicted feelings. https://www.walkscore.com/people/329000949391/aviator-game

I was excited to uncover this page. I need

to to thank you for ones time for this wonderful read!!

I definitely savored every bit of it and I have you saved as a

favorite to check out new stuff on your website. https://linktr.ee/aviator_games

Wow, this article is fastidious, my sister is analyzing such things, therefore I aam

going to inform her. https://steemit.com/game/@benjamin2bennett/myths-and-reality-about-gambling-exploring-the-thrills-and-risks

awesome

My relatives evewry time say that I amm killing

myy time here at net, except I know I am getting know-how daily bby

reading thes good content. https://affiliates.trustgdpa.com/time-tested-methods-to-essay-writing/

Your style is very unique compared to otyer folks I’ve read stuff from.

Many thanks for posting when you’ve got the

opportunity, Guess I will just book mark this site. https://nivanda.com/index.php?page=item&id=403

I’m very pleased to find this web site. I wanted to thank you for your time just for

this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoyed every little bit of it and i also

have you saved too fav to check out new things in your site. https://migration-bt4.co.uk/profile.php?id=458928

My spouse and I absolutely love your blog and find thhe mawjority

of your post’s to be what precisely I’m looing for. Does one offer guest writers to write content available for you?

I wouldn’t mind publishing a post or elabgorating on many of

the subjects you write concernkng here. Again, awesome web site! https://ladder2leader.com/make-your-essay-writing-a-reality/

I leqve a leave a response whenever I especially enjoy a article on a website or

I have something to contribute tto the conversation. It’s

a result of the fire displayed in the article I browsed.

Annd after his article Food Secuurity in Kenya | Datascience Limited.

I was actually excited enough to write a commment 🙂 I actually do have

2 questions for you iff you don’t mind. Is it

simpl mme or do some of these responses come across as if they are

coming from brain dead individuals? 😛 And, if you

are posting at other online sites, I would like to keep up with everything new you

have to post. Would you list the complete urls oof all your communal sites like your twitter feed, Facebook page or linkedi profile? http://pendikescortbayan34.com/author/sebastianha/

It’s impressive that you are getting ideas from this piece of writing as well as from

our argument made at this time. http://alpervitrin40.xyz/author/zenaida0085/

With havin so much content do yyou ever rrun into any issues of plagorism or copyright infringement?

My site has a lot of exclusive content I’ve ither authored myself

or outsourced but it looks like a llot of it

is popping it up all over the internet without my agreement.

Do you know any methods to hdlp stop content from being ripped off?

I’d definitely appreciate it. https://cityonlineclassifieds.com/index.php?page=user&action=pub_profile&id=25314

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts on this sort of space .

Exploring in Yahoo I eventually stumbled upon this

site. Reading this information So i’m haopy to convey that I’ve a very good uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed.

I so much undoiubtedly will make certain to don?t forget this website and provides itt a glance on a continuing basis. https://affiliates.trustgdpa.com/essay-writing-for-freshmen-and-everyone-else/

Hello friends, its imppressive piece of writing about educationand

entirely defined, keep it up all thee time. http://forum.altaycoins.com/viewtopic.php?id=840181

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican pharmacy – mexican drugstore online

buying nolvadex online

mexico drug stores pharmacies: cmq pharma – best online pharmacies in mexico

buying prescription drugs in mexico

https://cmqpharma.online/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

purple pharmacy mexico price list

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://cmqpharma.online/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies

buy sildalis

how much is clomid prescription

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know

a few of the images aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but

I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different

web browsers and both show the same results.

valtrex canada

price of 21 acyclovir 400mg tablets

advair hfa

It’s an aweswome artihle designed for all the internet people; they will

obtain benefit from it I am sure. https://www.provenexpert.com/en-us/aviator-game3/

When I initially left a comment I appear to have clicked the

-Notify me when new comments aree added- checkbox and from now on whenever a comment is added I get

four emils with the exact same comment. There has to be a way you are able to

remove me froom that service? Thanks! https://www.provenexpert.com/en-us/1xbet-aviator-game/

Hi there, I believe your blog could possibly be having web browser compatibility

problems. When I take a look at your blog in Safari, it looks fine

however, when opening in I.E., it’s got some overlapping issues.

I simply wanted to provide yoou wiyh a quick heads up!

Other thaan that, great blog! https://www.chordie.com/forum/profile.php?id=1895918

It’s amazing to visit tthis web site and reading the

views of all coolleagues concerning thjs piece of writing,

while I am also eager oof getting know-how. https://www.themoviedb.org/u/aviator-game1

Remarkabl things here. I aam very glad to

see your article. Thank you so much and I’m taking a look forward to contgact you.

Will you please drop me a mail? https://www.horseracingnation.com/user/aviatorgame

There is certainly a great deal tto know about this subject.

I lijke all the points you made. https://www.credly.com/users/aviator-game.38e3d3f0/badges

Its like yyou read mmy mind! You appear tto know a lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or

something. I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message

home a bit, but instead of that, this is magnificent

blog. A fantastic read. I will definitely be back. https://www.tumblr.com/farinell/746199571803308032/utiliza%C3%A7%C3%A3o-de-modelos-matem%C3%A1ticos-abordagens-e

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills as well as with the layout on your blog.

Is this a paid theme or did youu modify it yourself?

Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to see a great blog like this one today. https://wallhaven.cc/user/GeorgDerek

This tesxt is invaluable. Where can I find out more? https://leetcode.com/aviatorgameapp/

Hi there, I wish foor to subscribe for this blog to get

most up-to-date updates, so where caan i do iit please assist. https://www.wetravel.com/users/lucas-vision

My brother suggested Iwould possibly like this

web site. He was once totally right. This submit actually made my day.

Youu can not imagine simply how a lot time I had spent for this information! Thank you! http://fridayad.in/user/profile/2610726

Fantastic blog! Do you have any tips and hints for

aspiring writers? I’m hoping tto start my own blog soon but I’m a

little lost on everything. Would you recommend starting with a free

platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There

are sso many choices out there that I’m completely

overwhelmed .. Any tips? Cheers! https://passionatequran.com/blog/index.php?entryid=339

Thanks for another excellent post. Where else may just anyone get that kind of inforemation in such a perfect approach of writing?

I’ve a presentation next week, aand I’m on the look for such information. https://ada.waaron.org/blog/index.php?entryid=364

Appreciwte the recommendation. Let me try it out. https://srv495809.hstgr.cloud/blog/index.php?entryid=236

This is a topic that’s near to my heart…

Best wishes! Where are your contact details

though? https://srv495809.hstgr.cloud/blog/index.php?entryid=223

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if youu knew of any widgets I could add to my blog that

automatically tweet my newest twitter updates. I’ve been looking for a plug-in liike this

for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something likee this.

Please let mee know if you run into anything.

I truly enjoyy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates. http://demo.qkseo.in/viewtopic.php?id=834447

Normally I do not learn article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very compelled

me too take a look at annd do it! Your writing style hass been surprised

me. Thank you, very great post. https://forum.pgbu.ir/viewtopic.php?id=668

Great article, exactly what I was looking for. https://dev2.emathisi.gr/blog/index.php?entryid=396

Very shortly thiks site will bee famous among all blog users, duee

to it’s fastidious posts https://ada.waaron.org/blog/index.php?entryid=379

indian pharmacy online: online shopping pharmacy india – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

world pharmacy india indian pharmacy paypal indian pharmacy online

canadian pharmacy canada discount pharmacy thecanadianpharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

buying from online mexican pharmacy: best online pharmacies in mexico – medicine in mexico pharmacies

https://foruspharma.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

Heya i am for the primary time here. I came across this board and

I to find It truly useful & it helped me out a lot. I’m hoping to offer one thing back and help others like

you aided me.

mexican pharmaceuticals online medication from mexico pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy

https://foruspharma.com/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

reputable canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy online ship to usa – safe reliable canadian pharmacy

india pharmacy mail order: top 10 online pharmacy in india – pharmacy website india

onlinecanadianpharmacy canadian mail order pharmacy canadian world pharmacy

canadian pharmacy no rx needed: canadian drugs – canadian compounding pharmacy

india pharmacy mail order: Online medicine order – best india pharmacy

escrow pharmacy canada: canadian valley pharmacy – safe canadian pharmacies

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: mail order pharmacy india – Online medicine order

cheapest online pharmacy india top online pharmacy india india pharmacy

canadianpharmacyworld: legitimate canadian mail order pharmacy – canadian mail order pharmacy

https://canadapharmast.com/# canadian pharmacy no scripts

Greate pieces. Keeep writing such kind of info onn your blog.

Im really impressed by your blog.

Hey there, You have performed ann incredible job.

I will definitely digg iit andd in my opinion suggest to mmy friends.

I’m confident they’ll be benefited from this website. https://caramellaapp.com/milanmu1/1sqc5G5R0/iceland

Hurrah! After all I got a blog from where I be able to

genuinely take useful information regarding my study and knowledge. https://caramellaapp.com/milanmu1/w8SICmiSQ/iceland-gambling

When I originally commented I cliked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox

and now eahh time a comment is added I get four e-mails with the same comment.

Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Thanks

a lot! https://telegra.ph/Gambling-policies-in-Iceland-07-19

you’re in poiknt of fct a just right webmaster. The web skte loading speed is

amazing. It kind of feels that you’re doing any distinctive trick.

Furthermore, The contents are masterpiece. you have performed a fantastic job on this matter! https://scrapbox.io/bets-iceland/History_and_laws_of_gambling_in_Iceland

Highly descriptive post, I loved that a lot. Will here bbe a part 2? https://digital-techss.blogspot.com/2024/07/online-casinos-in-iceland-laws-and.html

I was recommended this website by my cousin. I am not sure

whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my trouble.

You’re amazing! Thanks! https://telegra.ph/Icelandic-Gambling-07-18

the canadian drugstore canadian pharmacy world trusted canadian pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – buying prescription drugs in mexico

indian pharmacy online: indian pharmacy paypal – top 10 pharmacies in india

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexico pharmacy – mexican pharmacy

http://foruspharma.com/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

online shopping pharmacy india: indian pharmacy paypal – india pharmacy mail order

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican drugstore online – mexico pharmacy

cheapest online pharmacy india: best india pharmacy – india pharmacy mail order

indian pharmacy online top 10 pharmacies in india mail order pharmacy india

canadian pharmacy drugs online: canadian 24 hour pharmacy – buy prescription drugs from canada cheap

mexican drugstore online mexico pharmacy medication from mexico pharmacy

http://canadapharmast.com/# safe reliable canadian pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

best india pharmacy: best india pharmacy – reputable indian pharmacies

Good day! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers?

I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any recommendations?

http://foruspharma.com/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

cheapest online pharmacy india: india pharmacy – top 10 pharmacies in india

canadian pharmacy online: safe online pharmacies in canada – canadian pharmacy prices

world pharmacy india: indianpharmacy com – online pharmacy india

canadapharmacyonline: canada drugs online reviews – buy drugs from canada

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# Paxlovid buy online

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline online sale

paxlovid pill: paxlovid for sale – paxlovid cost without insurance

can you buy generic clomid: clomid without insurance – can i order cheap clomid pill

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# where to buy amoxicillin

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# can you get generic clomid

buy paxlovid online: paxlovid covid – paxlovid cost without insurance

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# get cheap clomid no prescription

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# how to get generic clomid tablets

where to buy cipro online: cipro for sale – buy cipro online

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# 200 mg doxycycline

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline gel in india

where can i buy cipro online: п»їcipro generic – buy cipro online canada

where can i get clomid prices: cost of generic clomid pill – where to get cheap clomid price

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid covid

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline vibramycin

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# can i purchase generic clomid prices

paxlovid generic: paxlovid generic – Paxlovid over the counter

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# where to buy clomid tablets

clomid generics: where to get generic clomid – cheap clomid without dr prescription

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# order doxycycline without prescription

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro pharmacy

paxlovid generic: paxlovid covid – paxlovid for sale

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# п»їpaxlovid

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin canada price

doxycycline pills price in south africa: doxycycline 50 mg cap – doxycycline hyc 100 mg

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline for sale uk

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# drug doxycycline

amoxicillin 500mg capsule: amoxicillin 500mg capsule cost – amoxicillin 500mg capsules uk

lyrica tablets 100mg

п»їpaxlovid: paxlovid for sale – paxlovid covid

where to buy generic clomid online: can i order cheap clomid pills – can you get cheap clomid without prescription

where to get clomid pills: can i get cheap clomid without prescription – how can i get generic clomid

no prescription lasix

average cost of generic zithromax

Wow what you wrote is amazing thank you for sharing it. I just recommend to you this is the casino online game, it is not a scam promise, it will help you what the casino really is.

ciprofloxacin generic price: buy ciprofloxacin over the counter – antibiotics cipro